In-betweenness: Young Latinas and Identity

Edna A. Viruell-Fuentes’ qualitative research suggest that for Latino women the stress involved in negotiating ethnic identity under a stigmatizing environments might be one of the ways in which living in a racialized society affects health outcomes. Focusing on young Latinas poetry, whether written or spoken found online, this blog illustrates the complexity, and multidimensionality of forging identity as young Latinas within a stigmatized U.S. social environment and how this process seems to impact their emotional wellbeing. It also highlights the centrality of the social-historical context in the identity formation process.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In an earlier post, ”To what culture would Latina suicidality be bound?”, I presented a number of perspectives on acculturation, some of them more mainstream than others. A number of these perspectives question the universality of the acculturation processes as proposed by Barry et al. As a cross-cultural psychologist, Barry as well as other authors assume that culture is a variable that shapes and molds the “psych” unit of mankind: a core, essential self that has an independent, objective, universal reality, the “psychological processes that are characteristic of our species, homo sapiens, as a whole” (p. 4). On the other side of this argument, cultural psychologists tend to assume that their findings and theories are culturally variable, that culture is not an independent variable, and that psyches and cultures are in a cyclical, transactional relationship in which culture shapes individual minds and behaviors as much as the minds and behaviors shape the culture. However, the question of how the culture of psychology, psychiatry, and mental health in general interacts with the creation of practices and knowledge has been for the most part left untouched.

In writing this post I made some methodological decisions to counteract the invisible grasp of my own professional culture. I decentered the voices of practitioners, journalists, and academics by bringing the voices of young Latinas to the discussion on equal footing. I emphasize the importance of their voices and of their roles as the authors of their own experiences.

Douglas S. Massey and Magaly Sanchez R. from Princeton University have been searching for new avenues to document the human dimensions of growing up as an immigrant, whether first- or second-generation. They, indeed recognize that these experiences are not always evident in “objective” statistics.

These authors believe that

“Ultimately, identities are not readily observable: they are constructed in the thoughts of individual migrants who struggle to make sense of the circumstances in which they find themselves. What is needed is a means of gaining access to the perceptions of migrants without the intervening filter of researchers, who inevitably bring their own biases and preconceptions to the task”.

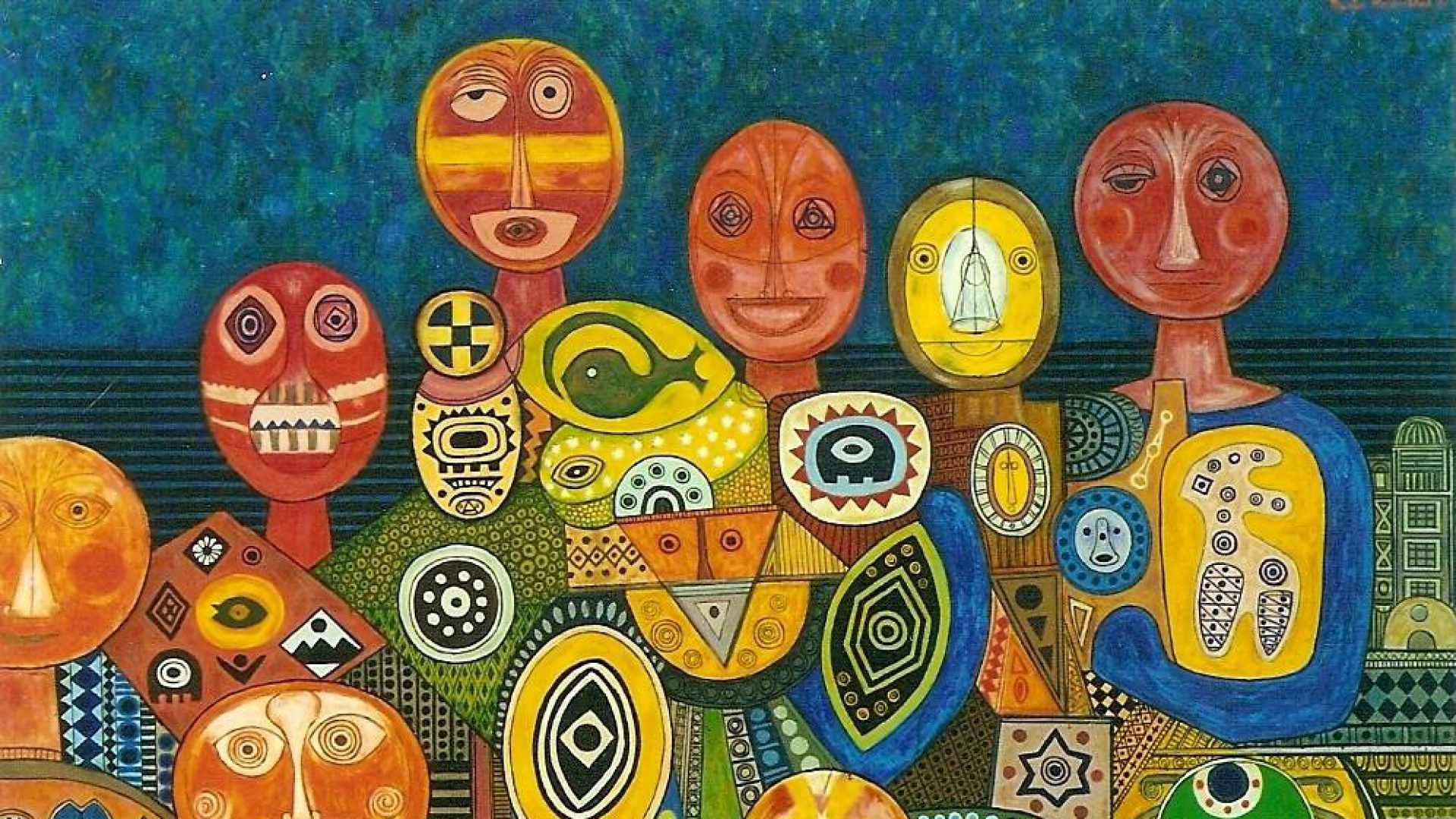

I couldn’t agree more. It has been said that artistic expression, whether painting, writing, or performing has been more successful in capturing the complexity of the intersection between human development and immigration than researchers and theoreticians, and I wanted to explore young Latinas’ identity beyond statistics and research. At the same time, social identity formation in adolescents is a multi-layer complex process which takes place in a context, one that the authors of the following artistic expressions clearly identified. A balanced conversation about this topic will also call for frequent attention to what has been written in academia.

The decision to search online for artistic expressions by young Latinas about their identity struggles paid off. I found several pieces speaking to salient aspects of identity which seem to be the backdrop of much of young Latinas’ emotional narratives of pain and suicidal feelings. It was a wise decision, since in terms of the use of digital media, Latinos have been called a marketers’ dream: they are digitally savvy, young, and socially connected, and young Latinas are no exception. They have taken the digital as a vehicle of expression. The massive flow of transmigration and border-crossing allowed by the internet parallels the experiences of constant shifting and in-betweenness expressed in their digital works. In the middle of this fluid picture something remains stable: a sense of cultural loss and an ongoing mourning experience. It seems that the digital has become a bridge—a “linking object”—for Latino cultural mourners, especially for second- and third-generation immigrants.

i am latina and i live

By Gabby Rivera (“a round, brown loverboi living in Brooklyn, NY”)

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT OF SUICIDE

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT OF SUICIDE

THIS MEANS

I

AM

A

LATINA

THAT

HAS

THOUGHT

ABOUT

KILLING

HERSELF

BREATHE THIS IN WITH ME

I

HAVE

THOUGHT

ABOUT

TAKING

MYSELF

TO

THE

END

and i wished it to be so

look me in the eyes

and think about what you see, think about what you see, what you see,

what do you see

i am nothing most days in the street

i am nothing

i am no one in these new york city streets

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING HERSELF

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING HERSELF

i am not sofia vergara

i am not sofia vergara

i am not jennifer lopez

i am not jennifer lopez

am i latina?

am i?

what am i?

the dark comes to me on subway trains

i am awake rumbling home, i am alone.

i am alone

i live inside of the subway, i am afraid in my home

there is no one to catch my tears there is only someone who wipes them away once they’ve settled into the cracks and into the shit on the floor of the subway car

there is only that person who sweeps them into a bag of hot cheetos and dumps them into a black canister and this person wishes for a better life

one without my tears, one without everyones shit on the floor

but they don’t see me either

they don’t see me either

i am always on edge, i am always on a ten even when i could be a seven

no, i do not work here

no, i do not work here

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT SUICIDE

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT SUICIDE

PLEASE LOOK AT ME

PLEASE LOOK AT ME

PLEASE SEE ME

PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE

WHY DO I HAVE TO ASK SO NICELY?

when i don’t smile you are afraid

i am that latina girl at your white job, that is me, i am she and when she doesn’t smile you are afraid and you don’t know how to say it but she knows you are afraid cuz you are afraid because when she is tired she isn’t pleasing you, when i am tired i am not pleasing you and you are afraid and you are afraid

and you make me so so tired

so tired

so tired

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING HERSELF

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT KILLING HERSELF

PLEASE LOOK AT ME

PLEASE LOOK AT ME

i am not cleaning your house, my mother is not cleaning your house, my grandma isn’t cleaning your house but you make more money than me, and you make more money than my mother and you make more money than my grandma and your money comes from them and your money comes from me and i don’t know how to fix it and i wish i could just fix it

still i am invisible unless i crack and snap and pop and lock, still i am invisible unless i crack and snap and pop and lock and make you laugh and make you feel better about your gentrification and make you feel better about your objectification and make you feel better about your colonization and make you feel better, feel better

because when i don’t smile you are afraid

when i don’t smile you are afraid

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT SUICIDE

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT SUICIDE

I AM LATINA THAT GOT TATTOOS TO COVER UP THE TIMES I SLICED MYSELF UP WITH A BUTTERFLY KNIFE TO FIND MY WAY OUT OF THIS COCOON

I AM A LATINA THAT GOT TATTOOS TO COVER UP THE TIMES I SLICED MYSELF UP WITH A BUTTERFLY KNIFE TO FIND MY WAY OUT OF THIS COCOON.

did you know that? bet you didn’t know that. how could you know that? what do you see when you see me? bet you don’t see the butterfly wings bet you don’t see that carcass of skin beneath my thick hips, bet you don’t see where i crawled out of the ground, bet you don’t see my birth, bet you don’t see that i was born,

bet you don’t, bet you don’t

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT THE END

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS THOUGHT ABOUT THE END

who has wanted so bad to be george bailey to lose hope on life and the world, to see how it doesn’t matter whether i live or die or had a wonderful life, who has wanted to stand on the edge a bridge and wait to see if an angel comes to me to show me my importance to say hey stay, to say hey fight, to say hey we need you, i am waiting, i am waiting, i wait. i wait for my movie ending. i wait for an angel to gets its wings because of me

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS NOT KILLED HERSELF

I AM A LATINA THAT HAS NOT KILLED HERSELF

i believe in the spiritual movements in the universe. i believe that my energy influences yours. i believe that spiritual violence lives in the air, i believe that we breathe it into our lungs and it finds itself in our dreams, i believe that whatever we put out affects those around us. i believe that you are drowning with me, that you are soaring with me, that you are standing on the edge of the bridge w me and we are holding hands, we are holding hands because if you’re not holding my hand then you are ready to push me off and i can’t believe that about you, i can’t believe that about you. i won’t believe that about you.

I AM A LATINA AND I LIVE

I AM A LATINA AND I LIVE

AND I AM ALIVE AND I KEEP ON LIVING

and you stand besides me because where else would you go because we share a blood line and a history and if it weren’t for your people and we are black people and we are brown people and we are mixed and we are yellow and mestiza and i belong to you and i belong to you and we are family, and our blood is red and some of my people belong to your bloodline and it’s a bloody mess isn’t it, but we’re all still here and this is my church and we are in worship and i honor you and i honor you and i honor and we will weep together and we will weep and i am weeping

AND I LIVE

AND I LIVE

AND I LIVE

I can’t help but remember Ntozake Shange’s play for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, when I read this poem. Gabby’s poem is, like Shange’s work, a feminist tale, where solidarity with others not only saves one’s soul, but also one’s life. The sadness, loneliness, and feeling of unimportance is palpable. But Gabby goes further; she makes a direct connection between her suicidality and the social context. She links the way she feels with the world she is engaged with. She associates the social inequalities she perceives in terms of class, race, physical environment, and gender expression with how self-destructive she feels. She perceives how others see her either as “nothing” or as a threat if she is not pleasing in her demeanor, when she is not subservient enough. She is tired of feeling objectified, gentrified, and colonized, and wants to end it all. However, Gabby believes that she is not alone; she realizes at the end of her poem that she is embedded on a web of solidarity. She believes that a mutual system of support with those who share her history and the mixed colors of her skin would keep her alive.

Research would agree with Gabby’s understanding of how the social and the psychological are connected. It has been shown that the rate of depression is significantly higher in Puerto Ricans than it is in whites. According to the authors of this research, a perceived low socioeconomic attainment and a sense of discrimination may be two factors that negatively affect the psychological status of Puerto Ricans living in the US and in the island. But for all Americans—not only for people from Puerto Rico, or for immigrants from other parts of Latin America, or their descendants living in the US—poverty is linked to depression, more than any other illness.

Gabby’s feelings and observations seem to also align with some researchers’ findings in the area of inter-group relations. According to these authors, people who belong to ethnic minority groups often perceive that others will reject them or be unwilling to accept them on the basis of their group membership, whether it is because of discrimination or lack of respect. These findings are consistent with research in social psychology showing that experiences in which one’s ethnic group is devalued can lead to negative self-perceptions and increased receptivity to mental and physical illness.

As Dr. Tony Iton, director of the Alameda County Public Health Department, explains in the acclaimed PBS documentary series Unnatural Causes, “If your environment is giving you the clue that you are not valuable, that you have very little prospect for a good future, that starts to build up, and you internalize that devaluation.”

The objectification, gentrification, and colonization identified in Gabby’s poem appear meaningful in the lives of some young Latinas. I will follow these threads in my analysis of the following three pieces of poetry and spoken word. These narratives are not directly connected to suicidality, but they are related to the struggle to belong and to feelings of marginalization, and therefore they are related to emotional well-being.

Mi Nombre

In this filmed reading of a text by Sandra Cisneros, the seventeen-year-old director, Astrid Maldonado (who is also one of the readers), creates a believable universe inhabited by those who live in it. From the beginning it is clear that this is not a singular story, but a story of many. The four girls take turns reading the story, in Spanish and English, and short shots of each girl reading are edited together with a match cut, preserving a sense of place and time.

In this video, the coming-of-age story of a Latina adolescent narrator living in Chicago in the early 1970s is appropriated by a group of 21st-century Latina high-school girls. Somehow, despite the wide generational gap, the story of Esperanza and her name seems to profoundly resonate with the struggles to become oneself for these young Latinas. Why? What is about this story that transcends time? For once, it literally crosses generations, including the narrative of a great-grandmother who was surrounded by melancholy and forever waiting by the window. The name, Esperanza, which means “hope” in English, also represents a connection with past cultural traditions embedded in a strongly patriarchal society —a society that did not allow women, even strong “horse women” like the narrator and her great-grandmother, to be what they wanted to be. Are these 21st-century teenagers afraid that something similar might hap pen to them? Do they feel that powerful forces, from known and unknown sources, might subvert their dreams about their future? If so, their fear would not be totally unfounded. They are, after all, girls in a persistently male-dominated social structure. However, the vehemence in the narrator’s voice as she expresses her desire not to repeat the past demands attention. She does not want to be prisoner of the cultural implications invoked by her name. Actually, she would like to have a new name that aligns better with whom she believes she is: her “real” self.

pen to them? Do they feel that powerful forces, from known and unknown sources, might subvert their dreams about their future? If so, their fear would not be totally unfounded. They are, after all, girls in a persistently male-dominated social structure. However, the vehemence in the narrator’s voice as she expresses her desire not to repeat the past demands attention. She does not want to be prisoner of the cultural implications invoked by her name. Actually, she would like to have a new name that aligns better with whom she believes she is: her “real” self.

The ongoing struggle produced by straddling two cultural worlds is called bicultural stress. Among Latino adolescents, this specific kind of stress has been linked to more depressive symptoms, as well as lower optimism among Latina girls and lower self-esteem for Latino adolescents (Romero and Roberts 2003a, b; Romero et al. 2007a, b). In addition, acculturation seems to be a more difficult process for Latina girls than for Latino boys. Girls seem to have a particularly difficult time navigating the gender-based expectations from their parents’ country of origin and the expectations from the host country (Zayas et al., 2000). There are also indications of the negative impact of sexism, gender identity, and gender roles on young Latinas’ mental health. In a study of depression and mental health in Latino adolescents, Cespedes and Huey (2008) evaluated the possible link between cultural discrepancies in regard to beliefs about gender roles and levels of depression, and found that these two factors are associated, and mediated by increases in family conflict. Cespedes and Huey argue that gender role discrepancy is associated with poorer family functions for girls, but not for boys. Both acculturation and gender-role discrepancy seem to have greater negative consequences for Latina girls. It is important to point out that Latina girls have reported one of the highest levels of depression, and that depression is considered one of the leading risk indicators for suicidality.

With its focus on transnational and dual identities, this video beautifully depicts the complexity of young Latinas’ experiences as they self-affirm, grow, and develop while straddling two cultures. But in the constant border-crossing of geographical, cultural, and language boundaries, in the back-and-forth movement between here and there, tensions, contradictions, and reconfigurations emerge. In turn, these emerging dynamics shape and influence the construction of identity.

HAIR

This video clip captures a different facet of the intricate prism described above. Poet Elizabeth Acevedo’s spoken word piece focuses on her body, where different races, cultures, and histories reside, but where her blackness is not welcome. Her “untamed” curly hair becomes the point of departure for an incredible poetic analysis of internalized oppression based on racial appearance, an oppression perpetuated by those near her, her own family, her own ethnic group, and the rest of society. This oppression negates the existence of parts of her body. It speaks of another of the invisible forces that threaten young Latinas’ freedom to become themselves. This time the focus is on how one should look in order to be accepted. The poem’s speaker is pushed to “fix” her hair, to gentrify it in order to reach the beauty standards expected from all.

Elizabeth Acevedo successfully fights these beauty standards in her poetry, but she is not quite as successful in her everyday life. The unwelcoming remarks from others have pierced her self-concept. It is as if these comments live within her. She continues to believe that her hair is not good enough, that it needs to be tamed to be elegant and sophisticated. She is in the process of embracing the message in the ending lines of her piece: “You can’t fix what was never broken.”

The topic of Elizabeth’s spoken word piece has been of interest to researchers. There is agreement among them that ethnic identity can be a source of resilience and strength for ethnic minority youth’s psychological adjustment. There is a small but growing body of research that suggest that physical appearance plays an important role in shaping experiences of ethnic identity. In a 2014 study, Carlos E. Santos and Kimberly A. Updegraff from Arizona State University documented that feeling less or more “typical” Latino in appearance has an impact on minority youth’s ethnic identity. Stronger ethnic identity serves as a buffer from the negative psychological consequences associated with rejection perceived in the larger society by members of an ethnic or racial minority group (Armenta & Hunt, 2009). Moreover, some studies have demonstrated that more African or indigenous racial phenotypes are associated with more discrimination among Latinos, and that Black Latino youth have significantly higher symptoms of depression than non-black Latinos (Burgo & Rivera, 2009). However, it is important to remember that Latina girls do not experience gender, race, class, and gender orientation separately: they experience the impact of all these social identities simultaneously.

Historically, Black identity in Latin America and the Caribbean—including the Dominican Republic—has been a source of intellectual, political, and cultural uneasiness. The discomfort with our mixture of bloods, african roots and slavery are carried from our countries of origin to this country, where a deeply embedded black-white dichotomous frame underlies most narratives of race, racism, and racial identification. In the United States, many folks from countries and islands south of the Rio Grande, especially those who are dark-skinned, find themselves having to choose among options which their historical experience did not prepare them to recognize. “Do you consider yourself more black than Hispanic or more Hispanic than black?” has the potential to be a disarming question for Afro-Latino Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and their descendants who live in this country. Given this historical and cultural context, it is easier to comprehend the profound meaning that Acevedo’s mother’s request that she “fix her hair” has in Elizabeth’s ethnic and racial identities.

How does the “typical” Latina look , sound, and behave?

The following spoken word piece by Mercedes Holtry, titled “My blood is beautiful,” complicates the answers to these questions.

Holtry’s poetry provides the perfect backdrop to continue to elaborate on the salience of race and skin color, as well as the experience of being mixed-race, to the social identity of Latinas. Let’s begin with an observation made by a French traveler, Louis Agassiz, who went to Brazil in 1865 on a scientific expedition. These are Agassiz’ words as cited by Thomas Skidmore (1974) in his book “Black and White: race and nationality in Brazilian thought”

“Let any one who doubts the evil of this mixture of races, and is inclined, from a mistaken philanthropy, to break down all barriers between them, come to Brazil. He [sic] cannot deny the deterioration consequent upon an amalgamation of races, more wide-spread than in any other country in the world, and which is rapidly effacing the best qualities of the white man, the Negro, and the Indian, leaving a mongrel nondescript type, deficient in physical and mental energy.” (p. 32)

This is not an old sentiment. A search for the term “mixture of races” online takes you to sites where racial mixing is both celebrated and rejected. Holtry’s and Agassiz’s words resonate with these opposite positions: Agassiz’s statement represents racist nativist ideology, while Holtry’s spoken word piece represents active resistance to the stigmatized meaning of her mixed blood. According to the Pew Research Center (2015), 34% of Latinos identify racially with mixed-race identities such as “mestiza” and “mulato.” I am surprised that this number is so low, given that mestizaje (miscegenation) has been rampant from the time of Latin America’s colonization, and has been historically embraced in many Latin American countries in nation-construction efforts. The Mexican philosopher Vasconselos’s idea of “La Raza Cósmica” conceptualizes mestizaje not only as a way to describe phenotypically Brown people, but as an example of racial harmony for the future of mankind.

The perspective of “La Raza Cósmica” was strongly contested by the policies of Blanqueamiento, or whitening—the social, political, and economic practices used in many Latin American countries to “improve the race” (mejorar la raza) towards a supposed ideal of whiteness, which is considered symbolically as a legacy of European colonialism. The conflict between this acceptance and rejection of racial mixing creates a vacuum where racial ambiguity survives. Mixed-race people create a problem for the United States’ Black-white system of racialization, which relies on phenotypes and skin color—as Holtry’s poem powerfully expresses. If you do not look either Black or white, what are you? This racial in-betweenness is the ambiguous, uncomfortable place where a large majority of Latinas/os racially sit.